Hello,

Welcome to KHỔ QUA, a newsletter by CÔNG TỬ BỘT. The restaurant is in the midst of a temporary closure at our physical location but open in a variety of different formats.

But what is a restaurant without food, you ask? You may no longer pay us to make food and bring it to your tiny table or uncomfortable stool. But this doesn’t mean we cannot continue to offer what restaurants also provide: intimate space, a space to explore new experiences. Space is not just the distance between us (six feet apart, please), space between us can be anything.

If you’ve ever encountered CÔNG TỬ BỘT in-person, you can expect KHỔ QUA will be similar in spirit: scrappy, determined, fever-dream spicy. KHỔ QUA will arrive twice a month with writing and images in assorted manifestations. Contributors come in the form of staff (we gotta get paid, y’all!), friends, and people we admire (fingers crossed!). We will explore various themes and questions that interest us.

This month, we consider the notion of UNCERTAINTY. From every promotional email we receive citing “these uncertain times” to truly what in the world is going on, we look at what UNCERTAINTY means to us. This issue takes on rambling, roving road trips across a burning country, Nixon’s last lunch in the White House, and naming as a means of certain fate.

And as always: no racists please,

Alana Dao, co-founding/managing editor

AN ODE TO UNCERTAINTY

By Corey Jennings

Part I

NO ONE can do it like you. Always within reach; always willing to give abundantly to anyone. You pull rugs from under the most expensive and well-upholstered achievements. But if not for you, who would dare to make a plan? I love you for what you are, Uncertainty!

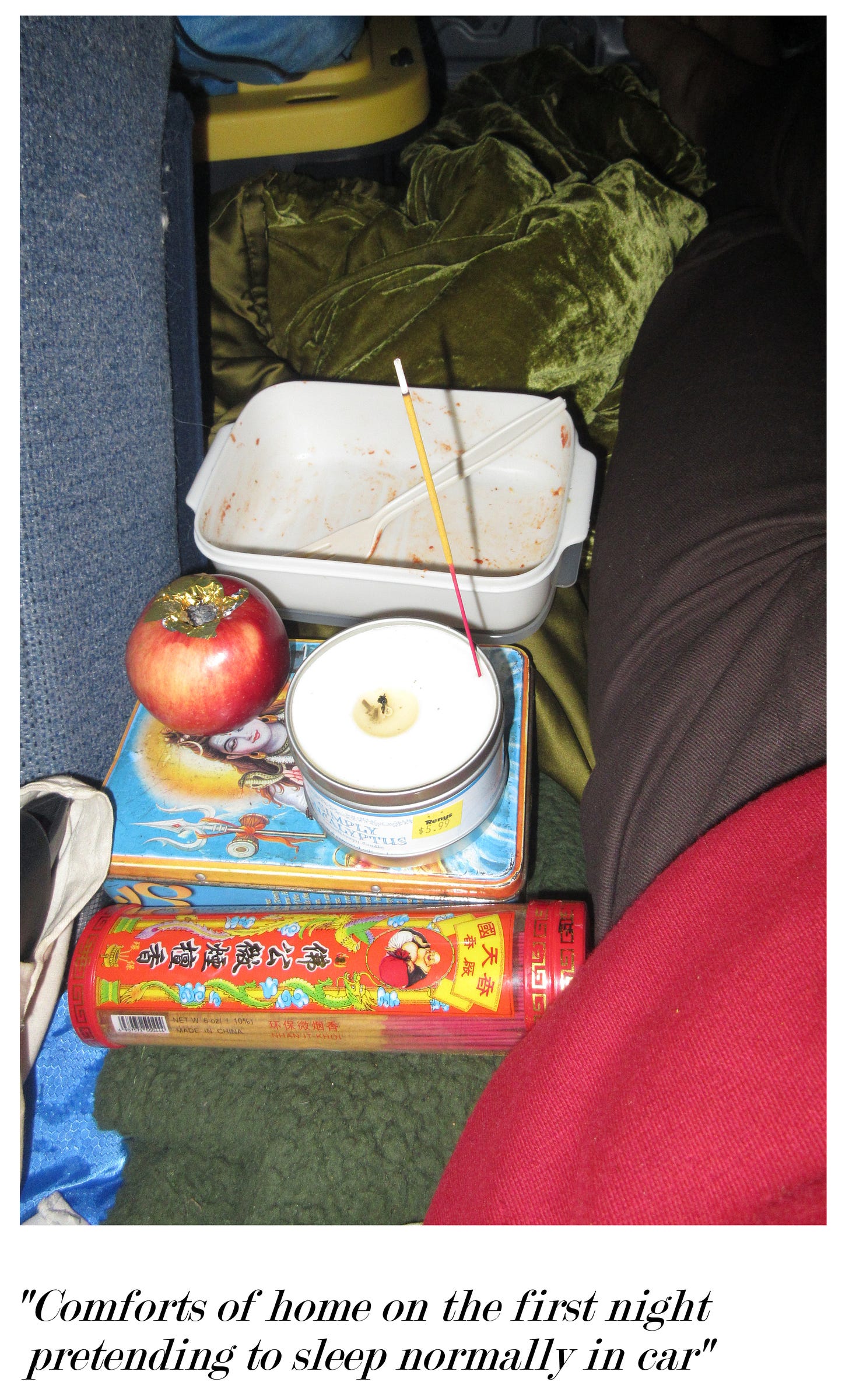

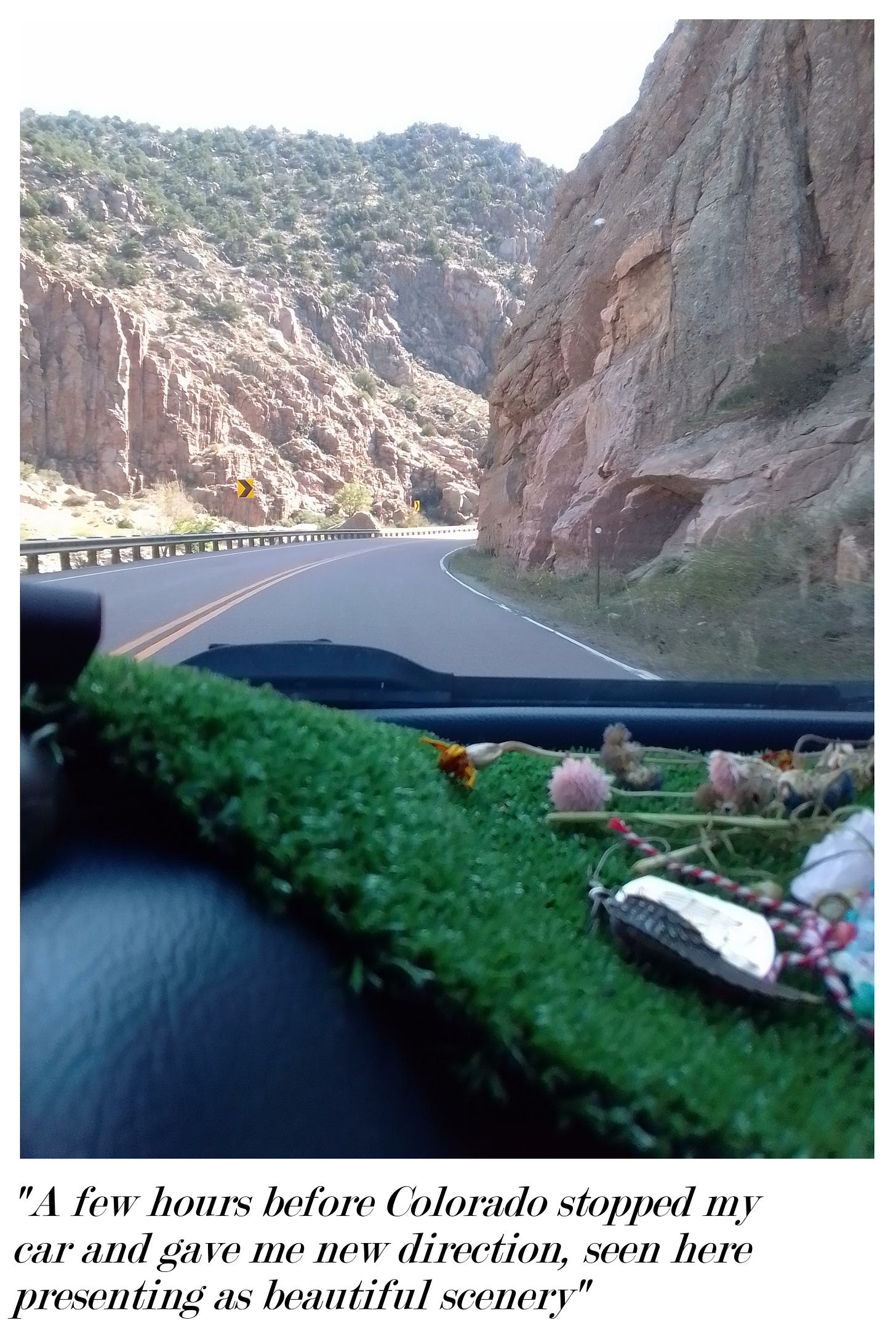

Left Maine alone without you, heading west for temporary work but you were waiting. Waiting to show yourself when least expected; car broke down in Colorado, car fixed in Colorado, all without ever visiting a mechanic.

MỘNG CHIỀU XUÂN*

by Bien Dobui

In France, the 2020 Coronavirus lockdown was called confinement. My own confinement had started a month earlier in February as I waited to give birth to my second child. When news of the lockdown was announced, our family of four-to-be folded into our apartment. Our five-year-old started having breakfast at 10 and day clothes were slowly replaced by a semi-pajama hybrid.

I knew abstractly that there was suffering in the world, that the virus was dangerous, that our elders were at risk. Not having the data, the pregnant were advised to stay home but given the low risk that children seemed to display, we were thrown into the same category: the baby will be fine, it’s grandma who’s in trouble. As with many others, our world was reduced to our home. Groceries became an expedition, screens had to be resisted like sirens; every day, I got heavier and slower. It felt like the whole world was expecting right along with us.

Our baby girl was born a week into spring, an hour into the day of my own birthday, March 29th. Everyone wore a mask though my husband eventually pulled his off midway. The only face my daughter saw for the first hour of her life was mine, as I softly sang “Happy Birthday” to us.

We named her Xuân, for ‘springtime’ in Vietnamese and planned to encourage non-Vietnamese speakers to use the pronunciation ‘swan’ a name that, though uncommon, also exists in French.

Mediating between our families’ three languages yet still honoring my Vietnamese heritage was important to us. We live in France near my husband’s family, and my family lives in the US. Vietnam was getting short shrift and I didn’t want to be the only person in our family of four to have a Vietnamese name, as if we were trying to erase that part of me in the following generation.

Thirty-five years to the day before Xuân’s birth, in a Los Angeles County hospital in California, my parents had named me Bien. Even though it was mostly a boy’s name, and a rare one at that, they liked it because it rhymed with Tien (my mom) and Vien (my older brother). It sounded both French (colonizers from the old country) and Spanish (a common language in the new country). However, if I had been born in France thirty-five years ago, my parents would not have been able to name their daughter ‘Bien’.

This is because until 1993, French parents could give their children “only those names cited in the [Christian saints] calendar and those of historically known persons...” in accordance with a law written under Revolutionary France. For two hundred years, if you were born in France a public judge had the right to tell your parents that if a name was foreign, not historically held in France, not found on the Christian saints calendar, or simply ‘not very Catholic’ then baby Glenn or Jasmin were going to have to become baby Jean-François or Marie-Chantal (the judges actually could– with recourse – decide the baby’s new name).

In the years after the 1993 law change, a variety of first names became more common, including non-French names (James, Yann), common nouns (Violette, Amour), popular figures (Sue Ellen from the soap opera Dallas, Dylan from Beverly Hills 90210), and names originating from one of many regional languages indigenous to France (the Catalan Llívia; the Breton Kevin). Current naming trends are a mix of classic names (Louise and Louis) and new vaguely Latin names (Mila and Maël).

Today, the state still has vetoing power though not against a name solely for its foreign or unprecedented character. A whole genre of popular media reports on recently refused names (Vagina, Nutella) confirm public opinion that parents just can’t be trusted not to expose their children to the ‘ridicule’ of a ‘vulgar’ first name, to borrow the current law’s language. Best to stick with Marie and Jean, the two most given first names since 1900.

After nearly two hundred years under the naming law, many French hang on to the belief that this freedom is a responsibility to be curbed so that children aren’t given names that would make them stand out in any way. A name seemed to hold a child’s fate in its preferably commonly held hand.

But what about the large parts of the French population who come from different religious or language backgrounds? In 2019, Mohamad was in the top 20 names given to little boys in France (it’s also the most common male first name in the world). It is estimated that a quarter of France has roots in immigration, and that in Paris alone nearly different 400 languages are spoken. However, this diversity is not reflected in our children’s names. In a 2019 article, the sociologists Baptiste Coulmont and Patrick Simon studied naming practices across three generations in immigrant families from different geographical areas. Those from Asia maintained their naming practices at less than 50%. And for all geographic areas studied, the following generation – meaning children with immigrant grandparents –bear names that are not French at only 20% or less.

Coming to France in 2005, I knew my first name was going to be at least a point of conversation, if not a source for mockery. Growing up named Bien in California where more than half of the population speaks Spanish, I had already been through those ropes. “Do you know that your name means ‘good’? Hey muy bien! Está bien, Bien? Hey, Good!” In France, people were mostly confused or wanted to spell it differently to match their pronunciation. Less often, but more memorably, a person would make something up that sounded like what they thought my name should be (Ping, Bing, Chong). In my experience, this wasn’t restricted to the French, but it surprised me in how unapologetic it was in an international city like Paris.

They seemed to be telling me it was somehow my fault - that my parents as twenty-four-year-old Boat People living in Southern California should have thought of how hard it would be for them, hypothetical French persons in an unknown future, to have to pronounce my name. It wasn’t very Catholic of them.

Similarly, I had been told when pregnant with my first child, not to give him a Vietnamese name so as to avoid hardship: ‘You’ll only make it harder for him later.’ Did they mean a Vietnamese name was ridiculous or vulgar? I could have just named him ‘Jim,’ closely homophonous for ‘vagina’ in Vietnamese. Or: ‘You shouldn’t make your kids carry your political convictions.’ Was there something political about being Vietnamese?

I began to understand that recognizing and feeling empowered by my non-European culture was political in a place where French conformity was considered the necessary ticket to assimilation. If there was a time and place to recognize being Vietnamese, it wasn’t up to me by choosing a Vietnamese name but to the majority society to concede. This happens at regular intervals. Once a man offered to switch his wooden chair for the plastic one I was on: ‘You’ll be more comfortable in it because you’ll feel like it’s bamboo.’ Another time, at the grocery store a woman asked if I could explain green tea to her.

As the confinement eased last May, we began to see more people. We introduced Xuân to her French grandma, her French aunts and uncles, cousins, and friends. Someone said, ‘You should have named her Rien (‘nothing’ in French) or Chien (‘dog’) to rhyme with your family’s names’(as it happens the latter is a real Vietnamese name, but I wasn’t going to give them the satisfaction). Seeing it written created a sense of insecurity. ‘But the ‘x’ shouldn’t be pronounced that way.’ ‘I can’t say it right. It’s too hard.’ People worried for her. ‘But imagine what it’ll be like for her at roll call on the first day of school.’

As a linguist and a university teacher, I happen to study language and languages in France. So, I’m aware that historically, the current writing system used for Vietnamese is based on the work of European Jesuits who used the Roman alphabet and French conventions. I’ve also done my fair share of roll calling. In Paris at a major public university, most names on my rosters were non-‘French’.

So, it didn’t seem like any of the criticisms were based on realistic concerns but were rather expressions of internalized monolingual and monocultural ideas of what a French person should be.

I think of the hundreds of languages co-existing in France, a country where French is constitutionally recognized as the sole language, and where policy for minority language recognition is regularly voted down. Of these languages, seventy-five are considered languages of France, including over thirty that are indigenous to metropolitan France.

In 1999, a French couple originally from Bretagne, a region of France where the Celtic language Breton is still spoken by some 200,000 people, was ordered by a court to change their son Kawrantin’s name. Kawrantin, they argued, is the Breton version of Corentin, a Catholic saint, and a name otherwise permitted. The judge allowed it, admitting he had been unaware of its origins, but a public defender appealed in a letter stating that a name with such a “barbaric consonance” could not be allowed. The original judgment was eventually maintained and baby Kawrantin was able to keep his name.

Even beyond the comments and misgivings I have experienced, a lot of work is still being done to maintain the illusion of monolithic French culture.

These days when we introduce our daughter, my husband has gotten in the habit of explaining our daughter’s name, then strongly stating how beautiful he finds it, perhaps in warning, perhaps as advice for best practice. One day soon, Xuân’s name will become normalized for the people around her and the uncertainty will dissipate. She’ll grow up and maybe by then, attitudes will have changed. After all, what's in a name? The power of change, like the seasons, like spring, like Xuân**.

*MỘNG CHIỀU XUÂN (A Spring Evening Dream) by LỆ THU, first recorded in 1975

**This last sentence is from a dear friend, who's expecting and knows only too well.

Uncertainty, oh you make family of us all! Showing your reach, nothing hidden. The consequence of your impact, consistent outside of my car, no change in frequency only in venue - I'm not sleeping well - but you excel in restlessness, I see that more clearly now.

A LAST MEAL IN POWER

by Vien Dobui

Photo: Robert Knudsen/Nixon Library

On August 8, 1974, this is what Richard Nixon, the most powerful white man in the world and our first explicitly “LAw aNd oRDeR” president ate for lunch: pineapple slices shingled around a golf ball of cottage cheese and a glass of tepid-looking milk. After this meal, he would go on television in front of his country to give up his immense power. Here’s how you, undoubtedly on the edge of your own steep precipice, can relive this very American meal in your own home.

Nixon’s Last Meal in Office

Interpreted from a photograph. Serves 1.

Ingredients

Canned pineapple, 2 rings

Cottage cheese, 3oz

Whole milk, 8oz

Method

Open a can of pineapple. Consider how unsurprising it is that Dole Foods, the primary exporter of pineapple from Hawaii for quite some time, has direct ties to the racist coup of the indigenous Hawaiian Kingdom.

Drain the swamp--I mean syrup and, even though this syrup can be saved to use as sweeteners in things like cocktails, discard it.

Remove two rings of pineapple, if there’s someone with less power and access than you within reach, let them deal with it.

Slice one ring into quarters, then cut a ¼ in off each quarter to make space between the rings for better shingling. Continue to discard what you don’t need, as though it never existed to begin with. Someone else can deal with it, right?

Arrange pineapple shingles onto a beige--that’s right beige, but khaki is also acceptable--plate. Maybe your Aunt’s wedding gift is within reach? Be careful to leave a hole large enough for a golf ball in the center of your collapsing pineapple infrastructure.

Open a tub of cottage cheese. Remind yourself that the current health trend of eating cottage cheese is in its second wave. The first wave being in the 1950’s, when Nixon was likely in his prime health, and a surplus of dairy products was repurposed into an endless campaign by the milk lobby to get people to consume more dairy. Time is a flat wheel of cheese.

Use an ice cream scoop -- another tool of the dairy industrial complex -- to form a ball of tightly packed cottage cheese. Place cottage cheese in the center of your pineapple log cabin.

Leave your milk out at room temperature for 2-3hrs. As you wait, consider that many immigrant parents (mine included) had their kids drink a glass of milk and eat a Kraft single every night before bed. It was one of the few moments my parents talked about not being “from here” while also expecting me to be grateful that we were here (though now I live in a state that considers me to be “from away”). What makes the myth of milk so persistent? That immigrant parents, even before the “Got Milk” campaign, believed in milk’s supposed miracles? That the Chinese government is now launching their own campaign to push milk as a novel coronavirus deterrent?

Pour milk into a clear glass, to best gawk at its whiteness and dominion over so many. Set it beside your plate of pineapple and cottage cheese.

Enjoy your lunch as best you can before you reluctantly hurl yourself toward the unknown of letting go of your power, the very power that disfigured you into believing that this meal could provide any comfort.

ROUNDING ERRORS

with Vien Dobui

Thanks for reaching the end of our first newsletter. Each issue will end with something like an update on what's going on around the CTB ecosystem. Maybe we’ll even give sneak peaks of some of the things we’re working on here too.

This week, we’re working on getting two big projects up and running for CTB: this newsletter and the very limited reopening of the restaurant (stay tuned!). There are some interesting intersections between the two projects. It wasn’t until we started working on the newsletter that I began to realize just how much writing and editing goes into how we approach restaurant work. From meeting agendas (we have lots of meetings here) and new safety policies to menu drafts and recipes, the actual creation--or in the case re-creation--of a physical restaurant starts with a lot of words. Likewise, working on the newsletter felt very similar to a large part of the day-to-day operations of the restaurant: lot’s of meetings, debates, and dialogue around food, race, equity, capitalism, and voice. You’ll probably hear us say it a lot but we really do think a newsletter is a natural extension of what CTB’s interests are.

Once these projects are functional, I’m very excited to think about how they might continue to interact and intersect with each other. Maybe we can share some of the documentation around recipe development in the newsletter. Or, when it’s safe, we could have a reading/speaker event in the restaurant. While these are fun but fairly obvious ideas, I’m really interested in the unexpected things that will grow from this new fertile ground (I haven’t even mentioned that we’re streaming on Twitch!) We’ve seen the results of professional publications that have their own amateur kitchens. What happens when a professional kitchen starts an amateur publication?

-Vien

CONTRIBUTORS

COREY JENNINGS (he/him, they/them) is a long time restaurant worker, exiled from Texas as a teenager. C is lost but not looking, and surely finding something. He is currently a furloughed line cook at CÔNG TỬ BỘT, our roaming correspondent, and banner illustrator.

He is currently eating: soup/stew straight out of the can, “salad kits”, cigarettes when I couldn’t find my food bag, chocolate chip cookies with my sister in West Texas, chocolate chip cookies and dumplings with my mom in North Carolina

BIEN DOBUI (she/her) is an associate professor of linguistics at the University of Picardie Jules Verne in France. She studies Mesoamerican languages and language migration into urban settings.

She is currently eating: lots of different beans in coconut milk, but I’m obsessed with what I call ‘emergent French’ foods, usually an existing non-French dish that’s reinterpreted by fast food, halal joints: tacos (a hybrid panini-burrito with fries inside), wings (anything breaded and fried, may not be chicken), cheese naan burgers, cheese sushi, etc.

Sign up now to get the next issue. You can pay (if you want!) but everything is free for now *wink* and don’t forget to tell your friends!