Hello,

Welcome to our first deep dive into JIGGLE. The word, the texture, the movement, has always been on our minds at CÔNG TỬ BỘT from the jiggly nature of chicken skin to the bounce and snap of a passion fruit jelly. It makes sense given that jelly has always been present on the menu. Made with agar agar, jellies have appeared on the menu in various flavors from mung bean to coffee and in various ways, whether alongside a bruleed banana or plopped into a flavored syrup.

But even beyond the actual making of them, we have noticed the snappy, soft texture and even the words “jelly” or “jiggle” in broader terms connote humor or immediately make us think of Jell-o, the ubiquitous substance most directly linked to a certain type of Americana. It felt inescapable and when thinking about the theme JIGGLE, we tried our hardest to avoid this direct link to Jell-o, the brand. It seemed too simple, too obvious. And yet. Despite ourselves, here we are.

As we swam further into the murky depths of all things jiggly, we realized that Jell-o with the capital J and its prevalence has had so much influence in how we in the United States interact with jiggly and gelatinous foods every day. Jiggly, bobbing, bouncy food entered our brains and souls via Jell-o and has never left.

We see this now, in particular, as glossy, gelatinous jelly cakes have become popular on Instagram. Seeing the smooth veneer of jelly make its way into our minds has provoked a lot of thinking and questioning amongst ourselves: what are we looking at? Why are jelly cakes appealing on IG while mung bean jellies are less so in a Vietnamese restaurant in Maine? Why does JIGGLE provoke such feelings? To look for answers we asked some of our favorite artists, writers, and jelly cake makers all about JIGGLE.

The jiggle has wiggled back into the forefront of our collective brains and so here we are.

As always,

Alana Dao, co-founding/managing editor

HE-JELLO-MONY

Words and interviews conducted by Alana Dao

I. Impeccably Molded

Jelly cakes, and by extension jiggly foods, can quite literally hold and embody a moment as inescapable and frozen in time. Jello captures objects such as fruit or vegetables, suspending them in space. And when we think about jiggly foods or jelly-like substances as subject matter, we also appear to return to a certain time era. Whenever we even bring up the word JIGGLE, the conversation always and inevitably turns to Jell-o, particularly in an American context. There appears to be something inescapable about those little branded boxes of flavored and colored powdered gelatin. My own first memories of jiggly foods are certainly of colorful Jell-o, perfectly cubed and gleaming in a plastic coupe at the Texas cafeteria chain, Luby’s. When I bring this memory up to artists and writers who I reach out to on the subject of jello, they all share similar sentiments.

That is because there is something mutually and universally understood about jiggly foods as a place for play and experimentation. Over conversations with writers and artists around the subject of JIGGLE, we dug a little deeper into what makes jello so riveting and universally nostalgic. What can jello and its ensuing texture, JIGGLE, mean for humanity, identity, labor, and gender? The histories of jiggly foods are fraught and intricate, filled with nostalgia, memory, magic.

When we spoke to artist and writer Sara Clugage, she explained to me the importance of JIGGLE through her artistic practice which often explores jello as material culture.

Alana (AD): How and why did Jello become part of your artistic practice?

Sara (SC): So much about gelatin is traceable through material history, but the aesthetic, sculptural qualities of jello make it more than the sum of its influences. There’s an irony and an irreverence to working with jello, but also a deep sensitivity to the human body and an urge for caregiving that means it is never only ironic.

Art and food have a lot in common as cultural products—they’re both practices of making that are informed by politics, economics, social castes, and trade relations.

AD: Your practice has been rooted in food, dinners, and history. Can you elaborate on your gelatin work as artistic practice?

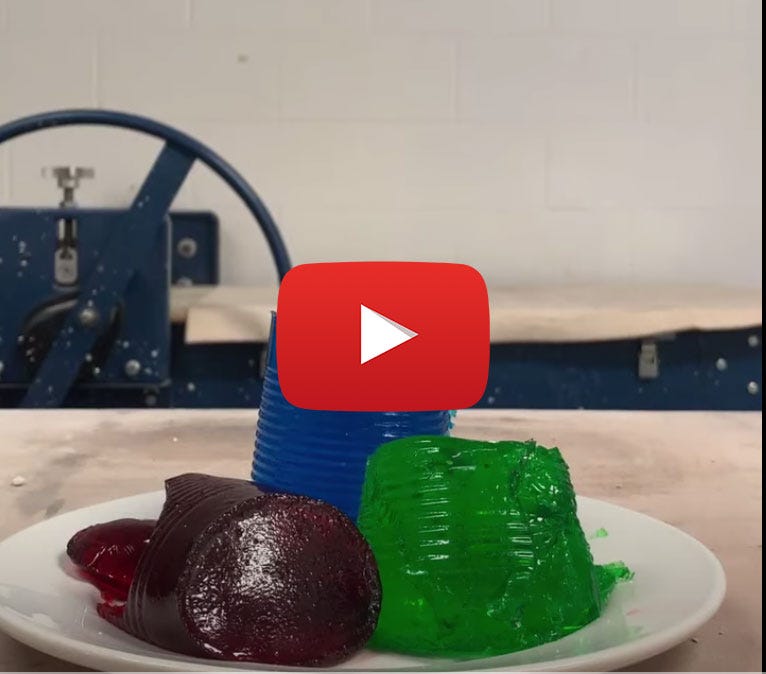

SC: Jello is edible, of course, but before you eat a brightly colored, impeccably molded piece, your first instinct is to look at it and touch it, even smack it so it wiggles. Jello is fun!

Because we experience it first as play and only secondarily as nourishment, the aesthetics of jello are different from those of other foods.

I would say that jello fits into the aesthetic category of the “zany,” following Sianne Ngai’s formulation of aesthetic categories, in that it has a sense of indeterminate and extended play. But it also fits into the category of the “cute”: it has connotations of care, femininity, and domesticity that encases jello in a soft shell of labor and unremunerated drudgery. The tension between jello as play and jello as care creates an anxiety that artists like me are anxious to explore.

AD: You have mentioned that “jiggly wiggly foods are impressively culturally complex.” Why do you think that is?

SC: When I look at the internet to see what people are saying about jello (meaning any jiggly food, including brand-name Jell-O and more broadly other jiggly foods made with gelatin or other setting agents like agar) the dominant tone is nostalgia. Jello nostalgia is a dream of a lost, perfect domesticity focused on the 1950s-1970s, the heyday of Jell-O’s mass media presence. Those memories can be endearing—lots of folks, including me, have family traditions around their grandma’s jello salad that signify home and belonging.

But the flip side of jello nostalgia is a longing for a blurry, mis-remembered 1950s America that included oppression and violence for multiple sectors of society along lines of race, class, gender, and sexuality.

It’s also a longing for a historically unique post-war economy that, despite the machinations of neoliberal politicians, is never coming back.

Jello in the United States is a convenience food. It’s ridiculously easy to make, something you would want when you’re too tired from working all day to make an elaborate dessert. Gelatin desserts in the late 19th and early 20th century were popular for their technological novelty—instead of taking three days to boil down your own gelatin from animal bones, you could make it in minutes using this magic powder. That magic-like ease and accessibility make jello feel friendly.

AD: Jello so often becomes sidelined for children and the sick but you also note that jello is a sign of hospitality. For whom and why do you think that is?

SC: Jello has a vibrant contemporary presence in North American food, especially in the South and the Midwest of the US. Fancy jello molds are signs of hospitality in that you make them for a party: they’re centerpieces, meant for display as much as to be eaten. While food trends might not currently include a lot of gelatin, jello still maintains its status as a “traditional” food, and so it appears in places where we value continuity and cultural memory, like holiday meals and state fairs.

Gelatin is definitely associated with children, which is a self-reinforcing effect of Jell-O’s advertising. Since Jell-O’s first ads in 1902, children have featured prominently. And it makes sense! Jello is more toy than food, after all, and this is a product for the domestic market—mothers are buying it for their children. I would say this has mainstreamed jello more than sidelined it. The only discourse that has sidelined jello is the art discourse, which is built around objects that can be disinterestedly contemplated from a distance, so that anything that can be touched or eaten is vulnerable to accusations of base appetites or sentimentality.

But sentimentality runs the consumer economy, and there is nothing more sacred to American culture than childhood.

Feminist artists have seized on jello as a way to critique gender-relevant concepts like femininity, childhood, and the domestic sphere; that the art world seems to periodically dismiss this as kitsch is a sign of the art world’s severe limitations.

AD: At CÔNG TỬ BỘT, we have talked a lot about gelatinous desserts that seem too “scary” or “weird”to certain people. We talk a lot about how much movement the word JIGGLE connotes,how its soft, wobbly texture seems to stand against the idea of efficiency, productivity, and streamlining systems that are markers of capitalism. Also, of the very Western/American ideas of “wellness.” Can you maybe tell us some of your thoughts about this in relation to your project with Jello industrialization and capitalism?

SC: The history of gelatinous desserts in East and South Asia is really different from North America’s. Powdered gelatin in the mid-19th century was so revolutionary to food culture here. But in Japan, agar-agar was first extracted from red algae in the 17th century and so gelatinous foods made from agar-agar have a deep and widely varied histories in Asian countries. Dotorimuk (acorn jelly) in Korea, kanten in Japan, and grass jelly in Southeast Asia all have longer stories than most jellies from European cuisine.

The value system is different in the US, which doesn’t have a middle market for gelatinous desserts the way that Asia does. We have down-market jello, and we have the occasional fine dining gelée (restaurants universally use the French word instead of the plain English “jelly” so that you know it’s high-class). But regular bakeries are not focused on jellies here, so it doesn’t surprise me that the average consumer would find it “weird.” Also take into consideration Jell-O’s role as a food for the dieter or the sick person—it’s hard to turn that corporate messaging around to make it seem like a decadent treat. In that sense, jello is very much about austerity and self-denial as a disciplined path to wellness.

However, the material qualities of jello transcend its messaging — it’s hard to take jello seriously as a disciplinary mechanism when it’s wiggling on a plate. Gelatin is a colloid suspension of proteins that resonates with the environment like our own flesh does, showing the effects of sound waves and environmental vibrations. Jello always seems at least a little bit alive. It seems like it’s enjoying life.

That pleasure in sweetness and movement is captivating. At the same time, gelatin is extracted from the skin and bones of animals in industrial-scale agriculture, processed by underpaid workers whose labor organizing rights are suppressed. The methods by which jello gets to your plate are extractive and cruel all in the name of efficiency. Jello embodies these complex truths.

II. Avant Basic

This idea of jello and play, jiggliness as “zany”, and sculptural qualities of jello is also part of what caught the interest of food writer, Bettina Makalintal. As a person whose job it is to understand and see many trends come and go, Bettina first saw gelatin work in the form of jelly cakes on Instagram and elaborated on what exactly caught her eye and why she thinks this trend will be around a while. Our conversation then turned to the idea of creativity, play, and community in the world of jelly cakes.

AD: How did you first become interested in jelly cakes?

Bettina (BM): I saw it as an extension of “Cake Instagram” (the nickname for the community of cake makers who share different aesthetics and tips and tricks via the social media platform) and I liked the sense of artificiality [it] evokes and all the experimentation and possibilities jello contains.

AD: Why do you think jelly cakes have taken off, especially at this particular moment?

BM: Jello is so tied to nostalgia but also there is a large community and it is a way to get really experimental in the kitchen. Some of these makers will also make cakes and give them away or donate to causes so they are also contributing to communities outside of Instagram.

AD: What do you think is so compelling about the texture and aesthetics of jiggly foods, particularly Jello and jelly cakes?

BM: It’s “avant basic” -- there are similar visual notes and while there is a sense of control brought on by its firm nature, jelly is still playful.

There is also the fine line between beauty and horror; it looks like food shouldn’t do that. There is horror and it is sexual in the way it touches and responds.

The aesthetic of jello is controlled yet playful visually.

AD: This is obviously part of the branding and market but what are other ways to think about jelly cakes or jiggly foods being subversive or non-Western centric?

BM: I think it’s a lot about pushback against this type of texture that has been deemed as strange or weird; part of the appeal of the actual irreverence of it.

Jelly cakes and jiggly foods as a whole play with what's appealing and unappealing.

What’s amazing about not just jelly cakes on Instagram but the whole jelly scene is that there is a more subversive community that plays with the chaotic and maybe not as beautiful parts of jelly art instead of just the hyper pretty cake. The messy, “gross” things you can do with jello will always be subculture to that versus jelly cakes.

AD: Do you think the pandemic has played a part in this trend?

BM: Yea, I think jelly cakes take a lot of time and labor; it’s not a set it and forget thing, it makes things a little more complicated. They are intricate and take a lot of time but are also really fun to discover different elements and are a form of escapism. I think this is going to become something we see a lot more of.

***NB: As we further investigate what gelatin work may mean to us now, we will continue to discuss jiggly foods’ past, present and future with Bettina in our next issue dedicated to jelly cakes and their makers.***

III. Embodiment of Innocence

This brings us back to the idea of jello as a play thing first and food second and all the implications therein that were simultaneously emphasized in Jell-o’s marketing. Children play to learn and work through who they are in the world, but adults play for pleasure. One such way to play, it seems, is jello. Bettina notes that this is part of the allure of Jelly Cake Instagram. Particularly during this past year when most of us lived, worked, and stayed at home, jelly work, both the making and sharing of it, can become a means for connection.

And so while Jello certainly embodies these complex truths, we may not have always been able to see past its voluptuous and expansive curves - its very nature obscures more serious subjects. It belies its links with, as Sara puts it, an “earlier period of mass industrialization, skyrocketing wealth inequality, and the development of mass media.” Jello’s qualities, from being nostalgic to its physical and unsettling jiggliness, distracts and allows for a type of forgetting while also reinforcing the trope that nothing is more sacred than Americana and childhood. Both ideas cling to an innocence that must be preserved - encased in gelatin, perhaps - at all costs. Once childhood is over, are we still longing to play? To forget the trials and tribulations of adulthood as a means to ignore the larger systems that crush us? In the midst of the pandemic, can we topple these Jello ideals to make way for a jigglier truth? Or do we continue to play even when we've finally understood the costs?

ROUNDING ERRORS

by Sara Clugage

CONTRIBUTORS

SARA CLUGAGE (she/her) practices art and writing that focuses on political issues in craft and food, recently centered on a series of salon dinners that examine economic models in art history. She is the editor-in-chief of Dilettante Army (an online journal for visual culture and critical theory), an organizer for the Wikipedia campaign Art+Feminism, and core faculty for the MA program in Critical Craft Studies at Warren Wilson College. She serves as a trustee for the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts. She is currently eating the braised lamb shanks with peanut sauce from Toni Tipton-Martin's cookbook Jubilee, lord it's good.

COREY JENNINGS (he/him) is the developer of the "no sleep, no problem" internal life coach technique and author of several Target credit card applications. He is currently working at CTB and freelancing as a VHS to DVD converter for hire. He is currently on a steady diet of baked rigatoni — recipe c/o the author’s flap of Rich Dad, Poor Dad — and hermit bars.

BETTINA MAKALINTAL (she/her) is a Filipino American writer based in Brooklyn, New York. She is currently a staff writer at Vice, where she covers food and culture. She is currently eating watermelon radishes and labne on toast. More generally, she is usually eating some combination of eggs or tofu; crispy, spicy sauce; and rice or toast.