Hello,

While it feels like there should be a little less UNCERTAINTY going around now that a certain election is over and done with (except for that whole potential coup thing), UNCERTAINTY continues to rage around us. However, these past weeks have given us something to work with.

I had the great pleasure of telling my daughter that a person of many firsts had been elected to the Vice Presidency. She, a six year old child of mixed race, had recently been asked by a classmate if she was born in Japan (she was not) and noted “I am the only Asian at school”. To be able to point to our VP-elect and say “she is the only and it is hard but it is also good” was something.

This news allowed me to tell my daughter of the daunting uncertainties I know are ahead of her but also show proof of the slices of joy in between. That while it may often feel lonely to be different, to be first, to be only in the midst of a certain kind of uncertainty, we can look to others.

So let’s get into it together as we continue to tag along on the Corey Jennings Road Trip Across America. Then find ourselves on new adventures like facing the uncertainty of imposter syndrome and the restaurant industry, encountering internet trolls, and thinking about the certain comfort of burgers in our new world of “pandemic pivots”.

As always,

Alana Dao, co-founding/managing editor

ODE TO UNCERTAINTY II

by Corey Jennings

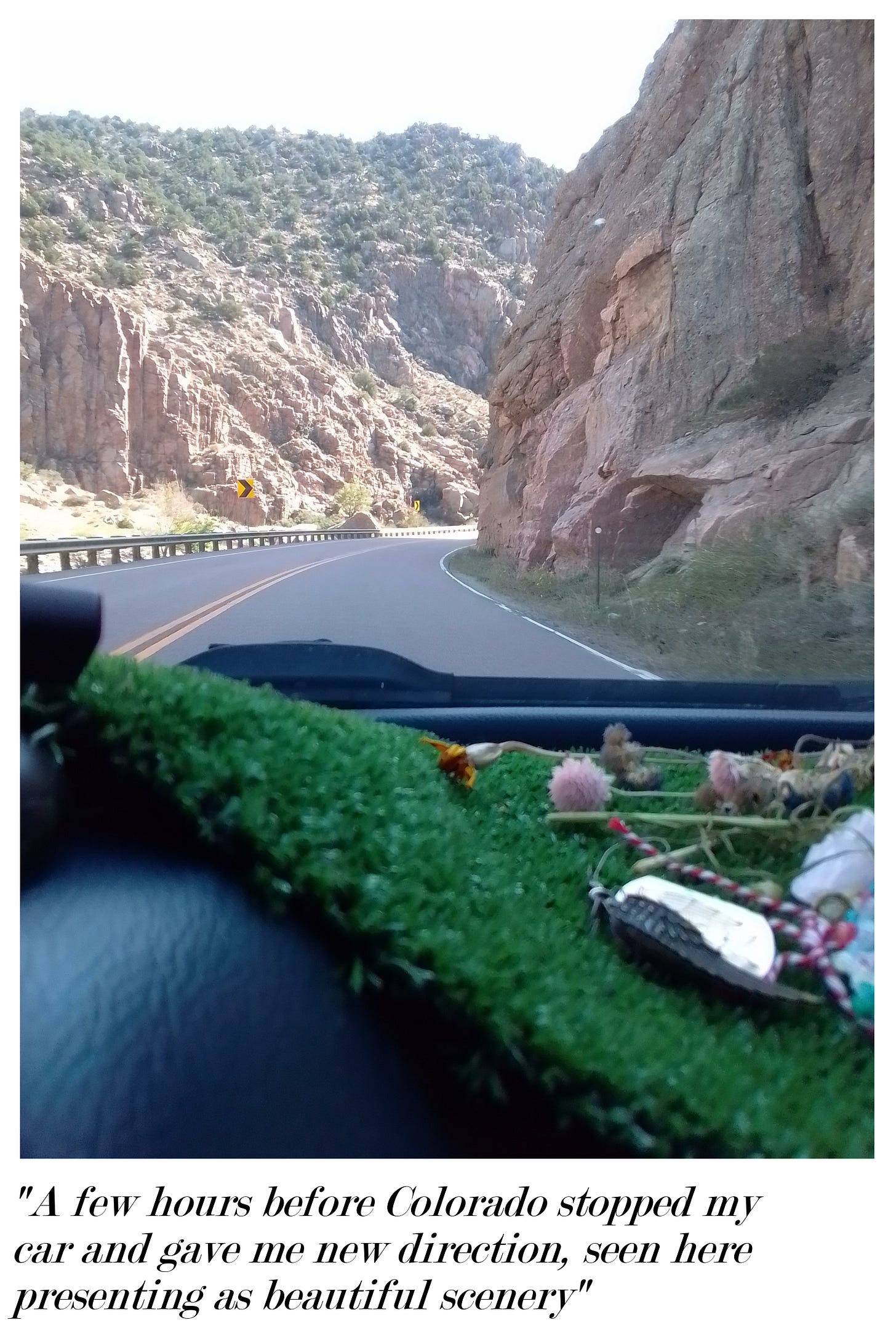

We continue on our trip with KQ’s rodent correspondent Corey Jennings across this burning country. We last left him at a crossroads, having to turn away from California wildfires and all that that was once promised to him: paid work, housing, a few weeks of planned adventure. What’s next? Where will Uncertainty take him?

You, ten toes in the minds of those who’ve suffered under you long before your most recent embodiment as droll leadership or global pandemic. You also, in the minds of those who’ve benefited too long from others’ muted existence. Or should I say, they’d be wise to consider you now more than ever.

SELF-DOUBT IN THE COVID ERA

by Katie Keating

I used to see impostor syndrome as largely a private, internalized thought process taking place inside the mind of individuals functioning under “normal” working (or learning) conditions. But it doesn’t form in a vacuum. Those of us who’ve encountered the debilitating self-doubt of impostor syndrome have had life experiences and relationships that led us to develop these thought patterns.

While we lay the psychological groundwork for developing imposter syndrome long before we reach adulthood, our experiences at work or in higher education also shape us. These experiences can easily reinforce not only our beliefs about ourselves but also our doubts about ourselves.

So many of us are conditioned to betray ourselves before questioning the systems within which we are made to feel inadequate because they are exclusionary by design.

Sometimes that betrayal looks like making yourself small, sometimes it looks like assimilating, sometimes it looks like remaining passive or neutral. But this is the kind of betrayal that takes place when a system itself is operating as it is meant to: in top-down, capitalist power structures that tend to reward privileged people while subjugating and exploiting lower-level workers. But what happens to our own personal self-doubt when the system is upended?

In 2014, I found myself looking for work in the restaurant industry after a several-year long hiatus.

I thought I’d left the industry for good—according to my family and amongst my peers, restaurant work was always to be looked down upon. Regardless of the skills I built or the obvious talent and grit required to succeed in restaurants, people in my life expected me to step away from it at some point to find a “real” or “better” career.

Thus, I returned to the field with not only some reluctance honed by the messages I was receiving, but also with a natural tendency toward self-doubt or impostor syndrome. I not only felt some shame for pursuing work in a field considered “unskilled”, I was also intimidated by the fast pace, the raw talent of the cooks and chefs around me, and the boys’ club culture I was expected to navigate.

My uncertainty around my ability to succeed in restaurant work doesn’t just have to do with my own thought patterns—it’s also the culture of the industry, which is predominantly white and straight and cis, at least when it comes to ownership and management.

My whiteness obviously insulated and privileged me over some of my colleagues but I was not spared from the sexual and gender-based harassment from my straight, cis-male colleagues and managers. I was hit on by fellow cooks while at work, then ignored once they learned I was queer. I dodged inappropriate comments from my chef who yelled at me until I cried and once told me, while I was in the process of deciding whether to take another position within the company, that one of my options was ‘to kill myself.’ I gritted my teeth and rolled my eyes while all the cis-male cooks in my kitchen decided our group motto was “don’t be a pussy.”

This is considered acceptable and common behavior in the industry, even among leadership. The specifics of the inappropriate behavior I witnessed and was subjected to are beside the point—they are just examples of business as usual: cis-male straight leadership, sexual and gender-based harassment, and poor boundaries, not to mention the rampant racism, which I have not experienced first-hand but only witnessed.

I was good at my job and worked diligently in an attempt to prove myself.

A few years in, after I’d gained some confidence in my skills and ability to withstand industry bullshit, I was promoted to a management position. Cue a new influx of impostor syndrome that continues to this day, some five years and two management jobs later. Who thought I was actually qualified enough to do this job? Oh right, my employers. But are they sure?

Fast forward to 2020 and I am two years into my job managing the back of house at CÔNG TỬ BỘT. I’ve found a more equitable and humane workplace, though I still struggle with feeling qualified to do the job for which I’ve been hired. Then Covid-19 entered the scene and the US' utter lack of strategy to successfully navigate it. Not only did I have to stay away from work, but so did all my industry peers. I was lucky enough to receive unemployment benefits relatively quickly so my worth and livelihood was, for the first time in my adulthood, not tied directly to my work.

Meanwhile, major industry call-outs were peppered into the chaos: Bon Appetit, Alison Roman, Danny Bowien, Angela Dimayuga, Sqirl, Diner, along with several lesser-known names, have been knocked from their pedestals by a critical audience and in many cases, their own BIPOC staff. And while these big names in our industry were called out or canceled, thousands of restaurant workers around the country lost their jobs either temporarily or altogether. Even the James Beard Foundation made the call to suspend its award season into 2021. We have begun to experience the death of the modern restaurant as well as the dismantling of the monolithic straight, cis, white, male chef as we knew him.

When your chosen industry crumbles before you on several levels - what are you left with? What happens when our industry implodes all across the country and we have to stay home? When the President of the United States turns out - though many of us knew this all along - to be the ultimate impostor?

What this whole storm did was leave room for those of us who had been in this grind for the past handful of years to stop. To look up from our knives and boards and reservation books and side work and say, “things don’t have to be this way”.

But how, then, will they change? Can we finally let ourselves find an answer and finally believe that we are not, in fact, the impostors?

CRUSHING AMERICANA

by Guy Lyons & Alana Dao

It is clear that the restaurant industry must adapt in order to stay afloat in this brave, new world. Some restaurants are selling groceries, others are take-out only. And another phenomenon has taken hold: the reappearance of the hamburger as an archetype of simplicity, of comfort and camp. Not that it ever really left us, but in places high and low, from Noma’s $20+ burger in Copenhagen to here in Maine, restaurants have begun turning to burger pop-ups as a “pandemic pivot” in the face of Covid-19.

Why now? Why again? What can the burger teach us about ourselves and what we presume we want or need in this particular moment?

The hamburger, once a humble item designed to cheaply feed the masses, has now become thrust into the spotlight yet again but revamped as “elevated”, smashed, dripping with that extra artisanal, housemade special sauce. It’s the American dream, right?

Will the burger ever stop being the symbol of Americana? It’s all simply too much! Better to just crawl under a blanket and stay home! Please, let’s all stay home.

Uncertainty! What to say of your loyal adherence to the security of everyone’s life to varying degrees. It's not for me to say!

ROUNDING ERRORS

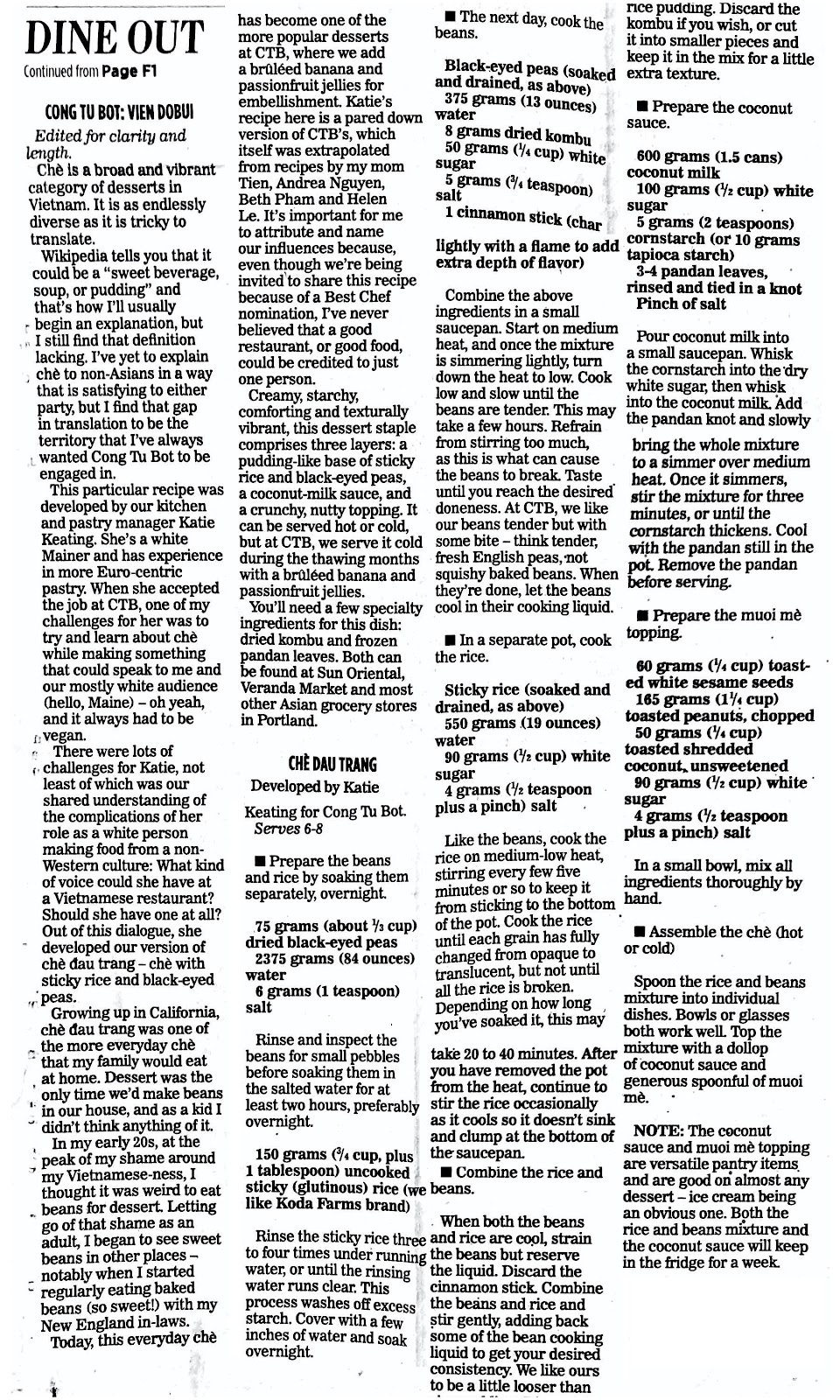

by Vien Dobui, Katie Keating, & Jessica Sheahan

To cap this issue, we’re including a recipe for chè đậu trắng that we did for the Portland Press Herald - look mẹ, we’re in print and on Substack - as well as a response to an annoying comment posted to the online edition of that same piece. Challenging as it is, we try to make a habit of not publicly feeding trolls and instead turn to one another at the restaurant to vent and unpack. But sometimes a little blood letting is good for the humors and when that’s done in a space that we’ve made for ourselves, maybe we’re just a tiny bit safer here than in the comments of our local paper.

We encounter racism too often in the every day existence of the restaurant, and in the interest of self-care, we sometimes ask our white colleagues to go get their people. So we asked our resident Entitlement Correspondent (and CTB co-founder) Jessica to respond to *checks comments* Steve. I assume that our anonymous online neighbor will never read this, but by responding here maybe Jess can talk some sense into the Steve in all of us.

- Vien

Hey Steve,

Nice one. You managed to yuck the yum of a dessert style found around the world with one line. It made us chuckle. What’d you eat last week that’s still looking so good?

My three-year-old son has similar reactions to new food at first sight. It’s true, we eat with our eyes first. I try to describe the new item in terms of food I know he likes, and it usually works. So Steve, I’m here to suggest the same to you. Do you like oatmeal? Baked beans? Banana splits? Then I have good news! You’d probably like this too!

I get it. You’ve never seen this dessert before. You’ve never seen these individual things put together like that. (Imagine encountering a Fluff-a-nutter for the first time!) It’s funny isn’t it, how we dismiss something because it doesn’t make sense to your lived experience. Even though we just read a story that rooted the food in tradition, but also in ambiguity, diaspora identity, and memory, we can’t quite make space for it if it doesn’t center around what we understand.

It’s a function of whiteness. Now, Steve, you might not be white, but whiteness touches us all, infects us all. It puts itself at the center of everything, and from there, it allows us to deny experiences - truths - even when the facts are laid out before us. It’s like the whole “well, I don’t see race” argument, used to center the experience of the respondent, usually white, to invalidate experiences of racism. The truth is we do see it. And you saw a group of ingredients put together in a way that felt foreign to you and maybe made you feel a little uncomfortable, so you clicked “leave a comment” to make sure everyone knew that Steve didn’t think it looked very good.

My son will often use the unknowingness of something to dismiss it. As I said, he’s three. He’s barely aware of the world outside of himself and definitely not aware of any impact he has on it. It’s just that, Steve, you’re not a child. I can’t guess at your age either, but I can call you childish. Whiteness delineates childhood experience and decides who gets to hang on to their innocence the longest. When we bring with us the assumption that the innocence bestowed upon us in childhood will also protect us as adults, we come to expect the benefit of the doubt. We claim ignorance, and we think that this ignorance justifies our denial of something. In her book Minor Feelings, An Asian American Reckoning, Cathy Park Hong says it quite perfectly, “Innocence is both a privilege and a cognitive handicap, a sheltered unknowingness that, once protracted into adulthood, hardens into entitlement.”

Entitlement, Steve - we figured it out! You expected one thing, you got another, you didn’t like it, you said something nasty. But what exactly made you feel so uneasy? Did it start when you read the headline and saw a bunch of words with accents? Or does your confectionery imagination end at whoopie pies and you didn’t want to be pushed early on a Sunday morning? Maybe you don’t have a “problem” with other types of desserts, you just don’t want them in your face. Well, Steve, it’s like I tell my son - take a deep breath and sit with your discomfort. If you speak less and listen more, you’ll probably grow up just fine.

CONTRIBUTORS

COREY JENNINGS (he/him, they/them) is a long time restaurant worker, exiled from Texas as a teenager. C is lost but not looking, and surely finding something. He is currently a furloughed line cook at CÔNG TỬ BỘT, our roaming correspondent, and banner illustrator.

He is currently eating: or rather, prepping massive amounts of food in an effort to recreate staff meal like his famous (to CTB) migas, roasted veggies, and tempeh in portions of 12, Trader Joe’s Elote chips, and probably more cigarettes

KATIE KEATING (she/her) is (was?) the kitchen manager at CÔNG TỬ BỘT and happily tagging along for the ride of whatever form this li’l restaurant takes.

She is currently eating: a lot of bread without shame, and regularly dreams about foraging mushrooms from the Maine woods and in the corners of her childhood bedroom (what's that about?)

GUY LYONS 2.0 (he/him) is a web developer and dad from Lubec, Maine, the hotly contested Easternmost point of the United States. He headed West to Portland (Maine) where he has cut hair, skateboarded in empty parking lots, made art, and tinkered with computers for many years.

He is currently eating: whatever Alana makes for dinner, too much chocolate, and the snacks that were intended for the kids’ lunches.

Sign up now to get the next issue. You can pay (if you want!) but everything is free for now *wink* and don’t forget to tell your friends!